Thursday, November 8, 2012

"Willie Boy", Harry Lawton: The Last Great Posse Chase

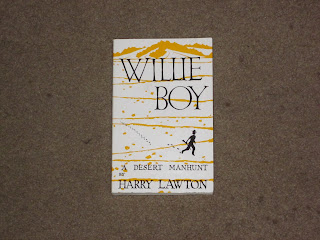

On a drive away from the Salton Sea and back to the Southland, our trip found us weaving through the Anza -Borrego State Park, and at a bookstore right outside the Martinez-Torres reservation, I found this book. The bewitching drawings on the cover and inside caught my attention. The story of the last great old west posse chase pushed me over the edge, and I eventually bought this edition.

Here's the title page:

Each chapter has a cool silhouette drawing that speaks to content of that particular chapter, and this is one of the coolest drawings, for chapter 10:

So...first the book, then the story.

The copy I have was one of the 1995 printings, the last time any press brought out an edition. Originally published in hardback in 1960, the subsequent paperback editions came out in '76, '79, '84 and '95. This copy has no printed ISBN nor a printed price. The last page is a fold-out map of the chase and surrounding area that if you're lucky enough to find a copy, you'll be using as reference regularly as you read.

The second-to-last page is a note abut the type, and it's here that they mention, in one sentence, that a man named Don Perceval "designed and decorated the book and jacket". That's how they mention, on the penultimate page, who did the silhouette drawings throughout. Perceval was a Brit, who gre up for a time in LA, and lived in the Navajo Nation for a time, and has a long history of Native American art pieces.

I was determined to buy a book at that particular bookstore, and this was my candidate. This book was first published by Balboa Island Press, and subsequently by the Malki Museum Press. Interestingly enough, the Malki Mueseum, on the Morongo Reservation, was the first museum on a reservation in America.

Willie Boy was a young Paiute man, living at the Twentynine Palms reservation in 1909. He was known as "Billie Boy" to everyone, and as a slight but hard working ranch hand and vaquero, he was well respected and liked by the white ranchers. He wasn't a drunk or gambler, but he did get arrested once for public drunkeness. The Paiute were a minority on the Twentynine Palms rez, but that wasn't the worst thing ever.

Part of those people's governing traditions that white American society today, as well as back then, didn't understand was what caused the so-called "last great posse manhunt of the west."

Marriage traditions are different all over, and things that happened for Paiute once occurred in what became the western marriage tradition---the act of marriage-by-capture.

Billie Boy ended up shooting Old Mike, the father of a young lady he had an eye for, Lolita, and then he and Lolita fled. The classic "Old West" was fairly dead at this point, but one more desert manhunt got organized. Ranch hands who knew Billie Boy were upset about the whole thing. They respected and liked him; he knew the desert, was a crack shot, and was fearless. This would be no easy manhunt.

Quickly they found Lolita dead, shot where she'd fallen, exhausted. An old Indian man shot by another Indian didn't stir up the blood, but a young dead Indian girl, one with designs on going to school, that got the public interested.

Posses formed in San Bernardino and Riverside, meaning to pinch him in the middle. President William Howard Taft paid a visit during the early stages of the manhunt, and since his nickname was "Billy Boy", the newspapers decided to call our fugitive Willie Boy. It was because of this speech tour and the attendant New York newspapermen picking up the manhunt story and spreading the word back east that made the story of a desert Indian's plight a legend.

Without the girl in tow, Willie Boy ran on foot for 500 miles all around the desert, from spring to spring, from food cache to food cache, never being caught by the horseback riding forces chasing him over pitiless terrain that would have killed most people. In the end Willie Boy took himself out with his last bullet and wasn't found for nearly ten days, ten scary days for southern California desert white folks who were sure a full scale Indian revolution was beginning.

His tale turned into a legend, and many stories about how Willie Boy survived and escaped into Mexico, or back to Nevada where he was born, or even all the way to Dinetah in the Navajo Nation abound in the lore of the desert people.

This book is just under a two hundred pages of text and twenty pages of photos, and, being written by one Harry Lawton, an award winning newspaperman (he was born in Long Beach) reads like a newspaper article and can be consumed in a single long afternoon, or over a rainy weekend.

The silhouette pictures by themselves are pretty damn sweet.

Quickly after this, manhunts were done by automobile and coordinated by telephone, and the idea of the horseback posse faded like the ghosts these riders were emulating. Many of the riders were friends with and contemporaries of the Earp family, and if the two sheriffs featured here, Ralphs and Wilson, were quicker to shoot instead of making peace during conflicts, they'd probably have turned into the legends of the dime novel story like their pals, the Earps.

Truly a fascinating point in this country's history, this little book is worth the look.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment