Monday, December 24, 2012

NY Giants: Super Bowl XXV Champs

In elementary school a trailer would show up at different times during the year. It was the book-sale mobile. I usually would get sports books, but one or twice I got a choose-your-own adventure. This is one of those sports books.

I was a Giants fan, and still am. Phil Simms winning his Super Bowl was one of earliest NFL memories. A few years later, during the Bills painful march through four straight Super Bowls, we got Hoss and Otiss (not a typo, that's two s's) leading Big Blue to another SB victory.

And as a modern fan, I've been able to enjoy Eli winning two rings himself. Two. Eli. Right?

This book is small and flimsy, maybe fifty or sixty pages, and is a collector's item, if that collector is a little kid who thinks the Hostetler name contains an interesting consonant cluster.

This is probably a time where I picked a book by its cover, like another one of my earlier book-mobile purchases, a baseball book from 1987 with Donnie Baseball on the cover.

Thursday, November 8, 2012

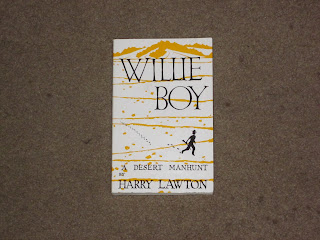

"Willie Boy", Harry Lawton: The Last Great Posse Chase

On a drive away from the Salton Sea and back to the Southland, our trip found us weaving through the Anza -Borrego State Park, and at a bookstore right outside the Martinez-Torres reservation, I found this book. The bewitching drawings on the cover and inside caught my attention. The story of the last great old west posse chase pushed me over the edge, and I eventually bought this edition.

Here's the title page:

Each chapter has a cool silhouette drawing that speaks to content of that particular chapter, and this is one of the coolest drawings, for chapter 10:

So...first the book, then the story.

The copy I have was one of the 1995 printings, the last time any press brought out an edition. Originally published in hardback in 1960, the subsequent paperback editions came out in '76, '79, '84 and '95. This copy has no printed ISBN nor a printed price. The last page is a fold-out map of the chase and surrounding area that if you're lucky enough to find a copy, you'll be using as reference regularly as you read.

The second-to-last page is a note abut the type, and it's here that they mention, in one sentence, that a man named Don Perceval "designed and decorated the book and jacket". That's how they mention, on the penultimate page, who did the silhouette drawings throughout. Perceval was a Brit, who gre up for a time in LA, and lived in the Navajo Nation for a time, and has a long history of Native American art pieces.

I was determined to buy a book at that particular bookstore, and this was my candidate. This book was first published by Balboa Island Press, and subsequently by the Malki Museum Press. Interestingly enough, the Malki Mueseum, on the Morongo Reservation, was the first museum on a reservation in America.

Willie Boy was a young Paiute man, living at the Twentynine Palms reservation in 1909. He was known as "Billie Boy" to everyone, and as a slight but hard working ranch hand and vaquero, he was well respected and liked by the white ranchers. He wasn't a drunk or gambler, but he did get arrested once for public drunkeness. The Paiute were a minority on the Twentynine Palms rez, but that wasn't the worst thing ever.

Part of those people's governing traditions that white American society today, as well as back then, didn't understand was what caused the so-called "last great posse manhunt of the west."

Marriage traditions are different all over, and things that happened for Paiute once occurred in what became the western marriage tradition---the act of marriage-by-capture.

Billie Boy ended up shooting Old Mike, the father of a young lady he had an eye for, Lolita, and then he and Lolita fled. The classic "Old West" was fairly dead at this point, but one more desert manhunt got organized. Ranch hands who knew Billie Boy were upset about the whole thing. They respected and liked him; he knew the desert, was a crack shot, and was fearless. This would be no easy manhunt.

Quickly they found Lolita dead, shot where she'd fallen, exhausted. An old Indian man shot by another Indian didn't stir up the blood, but a young dead Indian girl, one with designs on going to school, that got the public interested.

Posses formed in San Bernardino and Riverside, meaning to pinch him in the middle. President William Howard Taft paid a visit during the early stages of the manhunt, and since his nickname was "Billy Boy", the newspapers decided to call our fugitive Willie Boy. It was because of this speech tour and the attendant New York newspapermen picking up the manhunt story and spreading the word back east that made the story of a desert Indian's plight a legend.

Without the girl in tow, Willie Boy ran on foot for 500 miles all around the desert, from spring to spring, from food cache to food cache, never being caught by the horseback riding forces chasing him over pitiless terrain that would have killed most people. In the end Willie Boy took himself out with his last bullet and wasn't found for nearly ten days, ten scary days for southern California desert white folks who were sure a full scale Indian revolution was beginning.

His tale turned into a legend, and many stories about how Willie Boy survived and escaped into Mexico, or back to Nevada where he was born, or even all the way to Dinetah in the Navajo Nation abound in the lore of the desert people.

This book is just under a two hundred pages of text and twenty pages of photos, and, being written by one Harry Lawton, an award winning newspaperman (he was born in Long Beach) reads like a newspaper article and can be consumed in a single long afternoon, or over a rainy weekend.

The silhouette pictures by themselves are pretty damn sweet.

Quickly after this, manhunts were done by automobile and coordinated by telephone, and the idea of the horseback posse faded like the ghosts these riders were emulating. Many of the riders were friends with and contemporaries of the Earp family, and if the two sheriffs featured here, Ralphs and Wilson, were quicker to shoot instead of making peace during conflicts, they'd probably have turned into the legends of the dime novel story like their pals, the Earps.

Truly a fascinating point in this country's history, this little book is worth the look.

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Halloween Special: "Gotham by Gaslight"

This is a one-shot comic book, a graphic novel I suppose. Its popularity got DC comics to start what they called the Elseworlds imprint, a series of comics that were like what-ifs; basically characters out of the ordinary.

I bought this back in 1991, but it came out in 1989, and is one of the earliest works by pencil artists Mike Mignola, the creator of Hell Boy.

Like the Elseworld titles that followed, the basic premise of a well known character is tweaked. Here, The Waynes are London socialites around the latter half of the nineteenth century, and when they're gunned down, their son Bruce eventully adopts the mantle of the bat. As an adult, he hunts the baddies of the East End, and eventually is tasked with hunting down Jack the Ripper.

The story is fun and brisk, and because there aren't any real consequences for a beloved character, they can stretch and play. The art is moody and dark, and you can see what Mignola took from Frank Miller's 1986 classic The Dark Knight Returns, a watershed moment for comics that, along with The Watchmen, elevated the comic book artform to new heights. Mignola was an artist that was influenced, like almost everybody in the industry, by those two works.

This is good, and classic.

One of the Elseworld stories I don't think I have is one where Kal-El's space craft crashes and he's rescued by the childless Waynes, and is raised as their son, Bruce. He takes up the mantle after they're gunned down. How wild does that sound? Bruce Wayne is really Kal-El, and Batman has Superman's powers.

But it all started with "Gotham by Gaslight".

Thursday, October 18, 2012

"A-Rod: The Many Lives of Alex Rodriguez", Selena Roberts: Where's My Lawyer?

I've written about this book before, over on the original site. My mother found the book for ninety-nine cents at some place and sent it to me. I decided to write about it today to coincide with a sports blog post about A-Rod trade rumors.

So...let's say you play baseball. You play hard, you practice hard, you're kicking ass all throughout high school and for a quick year at college before getting drafted in the early rounds. Finally making it and becoming a star, you're financial power secured for generations.

Then a book is published claiming you used steroids all throughout high school and in college and in the pros. Ah hell no! I don't fucking think so! Time to put that financial power to good use. If you're clean, you're suing the writer, the publisher, the parent company, every-damn-body, right? I would. I would grind everybody's face to dust over that shit, just like Curt Schilling said.

That's what this book is about; the little child that was abandoned by his dad, always needing reassurance, always needing to be the best, and using every opportunity to get to that spot. Selena Robert's book alleges is pretty exacting detail how steroid use appears to have started for Alex Rodriguez in high school, and continued all the way through his years with the Yankees.

She spoke with him directly more than once, trying to get some kind of reaction from him...and got nothing. At least not in the form of contradictory fightin' words. Or lawsuits.

So take it how you want. I don't put stock into the "that's so wrong I won't dignify it with a response" line of reasoning. We're talking about a baseball player who's totally obsessed with his stats and his place in baseball's history and his legacy, and that these allegations could compromise all that, but he's already admitted to doping at one point! How hard is it to jump to the conclusion that this book is accurate?

Undeniable fact: A-Rod came back after an off-season during high school with more than thirty pounds of lean muscle added to his frame. The odds of adding thirty-plus pounds of lean muscle in a few months even for high school aged kids is pretty low (read: nigh impossible)(unless you're Andre the Giant, maybe).

Alex Rodriguez is strange case. His numbers are through the roof. But the Bronx fans...I've been at games where they boo him. Possibly the greatest player ever (before the steroid revelations, of course) getting booed at his home park. I've even been at games where he hits a homer, and was groaned at, a nearby middle aged lady hollering, "Do it when it matters!" with a shake of her head.

You can't be a fake asshole in New York. They sniff that shit out right away. And that's one of the main reasons they don't like the West Coast. Being a fake asshole is the leading industry in LA.

Friday, October 12, 2012

"Noa Noa", Paul Guaguin: Leaving it All Behind

I don't know where I bought this, but I'm sure I didn't spend more than a buck.

Paul Gauguin was one of the great initiators of Post-Impressionism,which makes him one of the fathers of Modern Art. Although he wasn't well regarded in his lifetime, now his works are sought after and prized.

Tired of city life in Paris, Gauguin left (as a forty-three year old), and went off to live in the South Pacific, specifically Tahiti. Pulling a "French Thoreau" I guess; going all the way to the So. Pacific.

The cover image from this copy is from a wood cutting from Paul's time during this, his first, visit.

At first he's disappointed. Europe has long fingers, and they've reached all the way to the Tahitian "metropolises". Eventually he gets further and further from the major towns, into the backwoods of Tahiti, which sound pretty fucking in the cut.

"Do you want to live in my hut for always?" is how he realized that the young beautiful native girl in his hut was now his wife. She was arranging food on a banana leaf.

The type set is strange in that the printed words may cover only slightly more than half the white-space on each page. But the tone, the angst, the feeling of leaving it all behind and fleeing for the tropics...that's the truth behind wanderlust. That's all there.

There's also the inevitable feeling of disappointment, since the world you're fleeing is too tempting not to replicate (it creates wealth), and thus infects anything of significant size.

Gauguin did it. He was one of the few that actually did it. This journal is breezy and quick, and as it unfolds, you can see his awestruck eye move into cynicism, and then into practicalities of life in the jungle.

It's one of the blueprints, if you're all about ditching your families and bills and running away to the jungle...at least philosophically, anyway.

Wednesday, October 3, 2012

"South", Shackleton: Boo Yah! A Story for the Ages

What's the craziest true story you've ever heard of? There are some wild ones, like anything involving either Nikola Tesla or Evariste Galois or Chuck Yeager.

Or Ernie Shackleton.

This book I bought somewhere after hearing about the story. I think I asked for it for Decemberween one year also, and I think I actually have two copies at the apartment. I think this copy has a font that's easier on my eyes.

Okay, so the story: this book is the memoir and partial journal of Shackleton's ill-fated journey to the South Pole.

It was the time of the last great explorers, and as the North Pole had just been mobbed, the South Pole was next. Shackleton's team was in a race with another team, a second team that, as a SPOILER, actually beat Shackleton to the Pole. In fact, Shackleton never made the Pole. But that doesn't matter to the story; it's incidental.

The picture on the front of the book is from their first trial, when their vessel got caught, and then crushed, in the pack ice miles away from shore. The crew drug the supplies--including the twenty-foot-long lifeboats--600 miles across the floes. Six-hundred-miles. When they got to a rock formation called Elephant Island Shackleton took three of his strongest men and set out again in one of those long-boats on a patch of sea. In order to save his crew, he knew he needed to get away from Antarctica, and cross the angriest ocean on the planet, the Southern Ocean, to get word out and have at least a chance.

The four of them rocked and rolled on unbelievably heavy seas in a 20' open long-boat---basically a glorified canoe. And they eventually landed on a small island near South America, were picked up by a larger vessel, went to Argentina, got supplies and another ship, and went back for the crew members that were left behind.

They found them, and saved them.

Ernest Shackleton did not lose a single man from his floe-crushed ship Endurance. They spent months surviving and waiting, and Cap'n came back.

If four guys riding sixty-foot waves of stormy frigid ocean for 850 miles in twenty-foot long open canoes doesn't get your excitement meter running, then you should stop snorting meth from bony hooker asscracks.

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

"Hell's Angels", Hunter Thompson: An Example from a Hero

I bought this copy in 2009 from the Housing Works bookstore in SoHo. I think it was a quarter. The cover wasn't as jacked up as that when I bought it; that all happened as I'd have the book in my pocket as I walked around. See, in the City, you need something to read on the subway, and I always tried to have a book or a newspaper handy.

Hunter Thompson is one of my intellectual heroes, and I've modeled different projects as direct inspirations from Hunter's work.

Hell's Angels is a history of the returning WWII vets finding solace in groups, all riding motorcycles like they had during the war. They took club names from their old military divisions, and occasionally got into scrapes with other clubs and small-town constabulatory forces.

They weren't always seen as a public danger. They didn't really keep up with society's level of hygiene, but they did enjoy a brief level of notoriety as being a public commentator of political issues--no joke.

The rise and fall of Sonny Barger's group, being invited to an unwitting Kesey acid party at La Honda, getting onto television and in print interviews was all pretty good and heady for the group. Then reports of brutal rapes filtered in, mostly unsubstantiated, and then a fight between two guys spilled over into a small coastal California town, and the Angels were from then on outlaws in the bad sense, not in the romantic good sense.

This book also showed off Hunter's take on Tom Wolfe and Plimpton's New Journalism. With the other proponents, Wolfe set about establishing New Journalism as a thing where writers could use the methods of story-telling normally reserved for fiction in telling a non-fiction story. Hunter's take on that topic is usually called Gonzo Journalism, but is only shown here in his approach. It was Hunter's contention that the author of any piece was inextricable from said piece, and would eventually become part of the story.

Tom Wofle's The Right Stuff is an example of New Journalism. Using plot and character development, Wolfe weaves an exciting story of bat-shit crazy test pilots fighting for the chance to sit on a rocket and light a match.

George Plimpton's One For the Record shows his attempt, an approach a little closer to Hunter's, where the author has a part in the story of one man and his attempt to survive his march to history.

Hell's Angels isn't Gonzo Journalism exactly, but how is it set up? Hunter joins them, and reports the world as how he sees it, not even feigning impartiality. He just accepts that being impartial is an illusion, and that's the legacy that I'm a part of, at least with the blogging anyway.

Monday, September 10, 2012

"The Game", Ken Dryden: One of the Best Sports Books Ever

I was reading out sports books online a few months ago, and came across a passionate fan of Ken Dryden's seminal The Game. I found it for sale online for very cheap, so cheap that the shipping cost more, something I've been finding lately with some of my purchases.

This copy was one of the Canadian paperbacks, which I thought was pretty cool, since this is one of the best selling books in Canada's history.

Ken Dryden played goalie for the Montreal Canadiens hockey team during one of their dynastic runs. The Canadiens are the NHL's version of the Yankees, having separate dynasties and winning the most championships in the league's history. Dryden went on to become a lawyer and lawmaker, and served in an elected position in their parliament.

The book was described by various sources as the best book about hockey by far, and possibly the best sports book ever. Well, I like reading, and I like sports, so there was the natural-ness of the whole shebang.

Reading in the introduction about how Dryden would scratch out notes on pads at his locker after periods, or on receipts or on random hotel stationary, but then he had a sickening realization that those thoughts and feelings he'd written wouldn't comprise a book in the sense he'd originally thought when he started the project. That topic is in the first few sentences in the introduction, letting readers know what they're getting into.

Touching on philosophy, memories, teamwork, leadership, and the drive for excellence, The Game is a classic in any discipline.

The last three books have been examples from my sports-book pocketbooks collections, and each covers a different iconic player from their sport: Hank, Pele and Dryden. This book is best of the three in terms of the writing.

"Pele: My Life and the Beautiful Game": The Greatest

This book was wrongly delivered to a house I lived in, and where we were in our lives, we opened the package up, and I ended up keeping it.

It's really good, and helped me understand Pele, Brazilian soccer, the late '50s through the '70s in international soccer, and the effect soccer---and Pele---has on the world, still today.

And that's pretty much it. This book has many pages for such a light collection of anecdotes. They're all very entertaining, and you get a tiny glimmer of what life in Brazil might be like, a country that's not fed the politics of the threat of global war.

In Brazil it's all about integration, dancing, soccer, and bathing suits made out of dental floss...a more magical place couldn't be created in fiction. Except for those murder rates...

Thursday, September 6, 2012

"Hank Aaron: One for the Record", George Plimpton: This is Why the Hammer is One of My Favortites

I can't remember where I got this, but I'm thinking I picked it up for a quarter or fifty cents from some paperback pile.

Oh man, oh man, oh man! I'm a baseball fan, and a Yankee fan at that, which pretty much makes me an asshole (I do my best to not be obnoxious), but I'd never really considered Hank for a top spot in my pantheon of baseball heroes.

That's changed.

Now I go and preach the merits of "the Hammer" to baseball fan and non- alike.

In this tiny book George Plimpton, of Mousterpiece Theater cartoons from the Disney Channel, of the New Journalism school of intellectual thought with Tom Wolfe, the Intellivision video game console shill, et al, focused his attention on the event of Henry passing Babe Ruth's career homerun record. It reads mostly like an article for the New Yorker or an artsy piece from Rolling Stone.

It's one of my favorite sports books: it's breezy yet deep, it never lingers, and it introduced me to a new world where Hank Aaron was one of the greats. I always knew that, you know, from the stats alone (when he retired he had the most homeruns, RBIs, runs, and was second for hits, and hit over .300 for his career). This book opened up my eyes to the visceral impact of his life (he started in the Negro Leagues!)(his life was threatened everyday for months) had on the game and America.

Plimpton, knowing that he has really only one fleeting moment around which to build an entire writing project--one pitch that gets hit over the fence for homer #715, eclipsing the Babe's 714 career mark, up to recently figured untouchable--decides to focus on different aspects of that fleeting moment.

His subjects are The Observer, The Pitcher, The Hitter, The Ball, The Retriever, The Fan, The Announcer. He visits a baseball factory; the guy who plays Chief Nok-a-Homer, the mascot in full headdress and costume; a wild fan in Atlanta that makes statues of Hank; Hanks's folks.

The world in which Hank Aaron played baseball was far different from today's. The country was still very segregated and it was more accepted to be obviously hostile and prejudiced toward black players. One of my favorite parts of the book is a telling quote from Hank's father:

"Henry was in baseball for work."

It was a job.

I've been one of the few who talk up Hank's status as underrated. The guy isn't ranked nearly high enough in most All-Time lists.

Go Hammer!

Friday, August 31, 2012

"Beowulf": Blood and Violence, Geat Style

I'm pretty sure I procured this from the book warehouse where I worked one winter season. I knew that I would want it for my library. I didn't read it for almost ten years.

It's very short, and this translation is brisk and breezy, especially for something so violent and gruesome. On my 30th birthday the missus had procured tickets to the Banana Bag and Bodice production of their rock opera "Beowulf: A Thousand Years of Baggage".

Having the copy and not having read it, I was inspired to read that year before going to the show. It didn't take very long to read. I always kind of found it weird that this was always considered an English work, rather, the early English work (besides Le Morte d'Arthur I suppose). But in the story, the hapless and helpless Danes need Beowulf's awesome ass-kicking force of Geats to help them with their demon problem, a sumbitch' named Grendel, and also his mom, who's kinda a pain in the ass.

I had to look up stuff about the Geats. They were a Swedish ethnicity, or at least that's what we'd call them now, and there is a state in Sweden called Geatland (I'm using the Americanized spelling). Now, the Swedes and Danes were mortal enemies for centuries, and the Geats wouldn't have called themselves Swedes by any means, but it always seemed funny to me that the Danes are depicted in this English story as being ineffectual. But why this is the tale that survives?

I'll tell you why: It's the same reason big action movies get made, or used to get made. It is unbelievably violent and gory. Like, holy shit man. Nobody ever told me. Granted, I don't read a lot of horror, or zombie fiction, but this was the goriest thing I've ever read.

Before Beowulf shows up to help save the day, Grendel likes to kill the Danes and eat them, and the description of Grendel working their bones in his teeth sounds like my cat going at a chicken wing, gnashing his teeth on them and grinding the bones down with greasy glee. When Beowulf makes it to Grendel's lair at the bottom of a lake, he's not as shocked as you or I might be to see that Grendel decorated the inside with the peeled skin of his slain victims. Wall papered his lair with skin and guts, man.

Beowulf, during a fight, tears Grendel's arm off and beats him with it as he's fleeing..

Awesome.

The story got me nice and amped for that rock opera, which didn't disappoint. f you ever get a chance to see it, you won't be disappointed.

Sometimes the classics are classic for a reason.

Monday, August 27, 2012

"Fields for President": Gin Blossoms for All

This copy of Fields For President, the one I bought from a tiny bookstore in the mountains of LA at a family reunion on my mom's side, was published in 1972 and aimed to be part of the campaign literature of that year. It was originally published in 1939. I bought it with another book, one about Kissinger called Superkraut that I've since lost. I think they were fifty-cents each.

WC Fields was a funny, funny man, and his humor translate mostly okay because of his mostly cynical and weary view of how government works. His view is also conspiratorial, one of the "the government is out to get me" types, but this attitude is laced with self-deprecating sardonic wit.

That's probably why it was re-introduced in 1972 early in that election year: it wasn't outdated. After a conversation I had with my godfather, the idea that films are harder to date when the protagonist is cynical and weary, whereas if they're happy-go-lucky, the times in which it was filmed shine through too brightly, and the piece become (often) badly dated.

With chapters titled "How to Beat the Federal Income Tax---And What to See and Do at Alcatraz" and "How I Have Built Myself into a Physical Marvel", you get a pretty quick idea just exactly where Fields goes with all this.

Full of pictures, it's an interesting artifact of a comic from an earlier time that knew what funny was, having found success in vaudeville, on the radio and eventually in films. Fields is mostly forgotten today, and I've yet to see if his movies are dated...judging by this book's sense of humor, they may have lasted.

Inside this book is an advertisement for Club Cocktails Whiskey Sour in a can, with two young people in swimsuits, wading in knee-deep water, sharing a can with two straws. (Shudder)

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

"A Night to Remember", Alfred Lord: Prose You'll Remember

Upon the centennial of the Titanic sinking, I read a few articles about the incident, and all pointed to Lord's A Night to Remember as remaining the authority on the event. There are other books, larger books, thorough books that explain exactly the second-by-second details of the last hours of the ship and her passengers, and they'd still refer to this masterpiece of cool, elegant prose.

I bought it for fifty-cents or something on Amazon, where the cost of shipping is more than the cost of the book.

If you care even a little about hubris and arrogance, about real-eyed honesty in the face of obvious destruction, about the unchaining of the poor (which of course happened far too late), I can't be any more blunt: READ THIS BOOK.

Lord spoke with as many survivors as he could visit in the '50s when he wrote the book, and the authority of the events is so confident and to the point that it blows the mind. The night unfolds with lightening pace from the first grinding sound to the surviving ranking officer getting sucked under and then blown out with a dying gasp of a sinking vessel. He made it to a capsized life boat, and stood until the sunrise.

The book is maybe 200 pages, and, if under the right circumstances, could easily be read in an afternoon. It grips you, and doesn't let go.

I think science has left the great majority of the facts stated here intact, which is to the credit of the memories of those who survived to tell the story to Al Lord.

Monday, August 20, 2012

"Hocus Pocus", Kurt Vonnegut: Nabbed from the Cuz

This is the first Vonnegut I read after reaching a maturity level appropriate to appreciate what he's doing. This copy I guess I stole, but mostly by accident. It was living at the house of the missus' cousin, where we stayed in Upstate New York when we moved Back East. I picked it up and started reading it, and must have gotten it mixed up with my own stuff, and it's been with me ever since. Down to Brooklyn, over to Austin, on to Long Beach...

It's a wacky one, for sure. The main character is a Vietnam vet who came back to work at a prison as a guard, and then is made a prisoner himself when the prisoners riot. Because he's not a violent prick guard, he's not treated too badly by the prisoners when they're in charge.

I may have made that entire synopsis up, and since the book is too far for me to get, I'm going to leave that as is. The veteran, as Vonnegut's politics would have suggested, had always felt conflicted about what he'd done or seen, and the position of prison guard was almost too ironic for him. I'm starting to think he was a prisoner there himself to start with...

I can't remember. I read it more than six years ago, and have had a few beers and Pynchon's in the time between.

In any case, one of the two more striking elements is that it's sections range in size from pages to lines. The premise being that he's been writing it on scraps of paper, and the sense you get reading it is a oddly paced confessional. The second element is part of the puzzle, and how the narrator frames it. Of his regrets, he realizes that the number of women he's slept with is the same number of people he killed in combat. This tidbit he mentions early on, but never states what the number is. Throughout the entire book. One of the very last things he says is an explanation, a rubric, for how to calculate the number, what pages to look on for the pieces to combine to get the answer.

I guess these little things are more review-like than I felt earlier.

Oh well. It was good. I liked it at the time. I'm sure it's not Vonnegut's best work, but it had an interesting pace and story design, and I would recommend it.

Making Some Changes

I've decided to make a few changes to how I title my posts. If you read this regularly (uhh, okay), you might have noticed the titles of the posts have been changed to reflect the title of the book and the author, if applicable, that will be discussed in the post itself.

I resisted that at first, as I didn't want people to come along the blog and think that it was a review site. Of course it wouldn't take too much reading to realize that this is most definitely not a book review site (I leave that for poppa Chef Gonzo), so I realized my worry was mostly unfounded. What not having the book titles in the post titles did do, though, was make everything cryptic when I was aiming for artsy.

Best laid plans, right?

Now at least a search of a title may direct some unwitting reader here, where they won't be getting a review, rather a narcissist's ramblings on how he acquired said book, either by buying or stealing, and what that person got from it, or the designs they made for it in his grand scheme, his Ganzebilde.

Okay. Moving on...

I resisted that at first, as I didn't want people to come along the blog and think that it was a review site. Of course it wouldn't take too much reading to realize that this is most definitely not a book review site (I leave that for poppa Chef Gonzo), so I realized my worry was mostly unfounded. What not having the book titles in the post titles did do, though, was make everything cryptic when I was aiming for artsy.

Best laid plans, right?

Now at least a search of a title may direct some unwitting reader here, where they won't be getting a review, rather a narcissist's ramblings on how he acquired said book, either by buying or stealing, and what that person got from it, or the designs they made for it in his grand scheme, his Ganzebilde.

Okay. Moving on...

Thursday, August 2, 2012

"The Savage Detectives", Roberto Bolano: Sexy Adventures of Mexican Poets

I bought this while living in Brooklyn, and read it mostly on the subway. At those time I would take the dust jacket off and leave it in my bookshelf to look proper, and over time the hard cover would become stained and shabby with the sweat and oils from my fingers and palms. I even wrote about this phenomena over at my oldest blog, complete with pictures of the damage.

I had read a review of this book, and of Roberto Bolanyo. He'd been a Chilean poet and author and had moved to Mexico and started a poetry movement. This book mirrors that scenario to a degree. The whole idea behind the novel, and its execution piqued my interest, and I went out and got it.

It starts out like a seventies coming-of-age/soft-core film, with a main character out writing poetry and trying get laid. He tries to ally himself with two older poets who have started a movement, one Chilean and one Mexican, and they have big plans: they plan on kidnapping Octavio Paz. There is so much discussion of seventies era new-world Latin American poets and poetry that it'll blow your mind. You don't really have to know anything about them to enjoy the story, but if you were familiar with it, the references would be awesome.

This section ends abruptly, on the eve of a big action set piece. The next two-thirds of the book is a series of interviews with folks who were tertiary characters in the opening section, and all taking place fifteen to twenty-five years later. Through the interviews the ramifications of the actions that hadn't occurred when the first section stopped are starkly apparent. How everybody reacted and the aftermath played over the years, the disappointment and regret, all laid bare.

A few things, though: the interviewers are never fully defined or introduced, and the main character from the first section, is mentioned maybe once during the long interview section, and that's way near the end.

When the interviews are over, and a couple of decades of living on the margins of society, as many non-famous poets are wont to do, are painted for the reader, the first section starts up again, right where it left off, and now it's like a seventies action movie. The events that are being investigated throughout the middle of the book are witnessed, and we see how events turned into anecdotes and then turned into stories.

It really is a good work, a nice work of fiction. I looked into but haven't yet procured Bolanyo's so-called masterpiece, the mysteriously titled 2666, a 900-page novel split in five sections and deal with European literature critics and Mexican prostitute murders, and they are all connected. In reading a review of 2666, the names of some of my favorite writers get mentioned (Denis Johnson and Murakami) and a few writers I've heard of but haven't yet gotten into (Don DeLillo, James Ellroy).

If you're looking for something else, somewhere to start in the newly discovered and ever-growing market of Spanish writing translated into English, The Savage Detectives would probably be a good start.

Monday, July 30, 2012

"Cloud Atlas", David Mitchell: Connections Through Time and the Ether

This novel by David Mitchell was another one of the "recommended by my dad" series while the missus and I lived in that tiny little back-house in our college town. I bought it in 2004 or '05. It is one I recommend to other folks all the time, recommend to kids who are inspired by my informal lectures about the differences between literature and genre fiction. Not all literature is stuffy fights between dysfunctional families. (Why is that what I think other people think literature is?)

So...Cloud Atlas.

This has been called a "nested puzzle-book" before, and I suppose that is an accurate statement. For anybody wanting a good book to get into, this one here is rewarding and exciting.

It starts out in the 1840s, and you're following a doctor on a whaling vessel, and the language in which it's written is just like it would be from that era. At the bottom of page 46, it stops mid-sentence.

The next section starts and it's presented as a series of letters from a musical conductor living in the 1870s Hapsburg Austria. The letters proceed for another 40 or so pages, until they end, and a section starts where a young lady is reading the letters. Her story is a pulpy '70s style detective story.

In the middle of the action that story stops, and we get the story of an older man who feel he's been wrongly committed to an elder care home. While he's plotting his escape, the story stops and we're sent to the future, where an uprising of the android/clones is beginning.

This sections stops abruptly and we get to a future way after the fall of civilization. This section doesn't end abruptly, it is twice the size as the other parts, and ends regularly. The next section wraps up the futuristic uprising plot, then the story about the man stuck in the home ends, and then the detective story ends and the main character goes back to reading the letters. Then we see the end of that Austrian conductor, and, in his last letter, he claims to have found the other half of the whaling ship novel.

The last section is the end of that storyline.

This novel has a direct influence on the novel I'm finishing the first draft of now, and I realized it after I excitedly watched the trailer.

That's right, this book is getting a big Hollywood treatment, and by the Wachowski Brothers (makers of the Matrix) to boot. Here's a link to the extended trailer on Youtube.

This book is just fun.

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

"Nobody Move", Denis Johnson: Easy Does It?

This is one of Denis Johnson's newest novels, being published in 2009. Johnson's one of my favorite authors, and a guy I try to emulate.

I bought it at the Barnes and Nobles across the way from the Union Square one Wednesday afternoon working for the dairy company.

It seemed like a pair of my authors were publishing books at the same time that were in the same vein. This entry from Johnson, and Inherent Vice from Pynchon, were those specific writers' feelings on genre fiction. Inherent Vice is Pynchon's play at detective novel, and this tiny tome is Johnson playing with a quick pulp crime novel.

This is a quick read. And by "quick", I mean it's like cotton candy and can be sped through in a long afternoon if you so desired. I liked it, but it didn't make me think of Denis Johnson inherently. It was generic for all I could tell.

Inherent Vice, which will be here someday, was at least noticeably Pynchon's work.

The title of this book comes from a line from a song that comes in over the radio during an early scene: "Nobody move--nobody get's hurt." The novel claims it comes from a reggae song, but I know it from somewhere else, an Eazy E song from the album "Eazy Duz It".

Tuesday, July 3, 2012

"A People's History of the United States", Howard Zinn: The Zinn Master

First, let me say that I know I don't have too many readers for this autobiographical blog about my library. And secondly, I apologize for the lagging...I went away to help my brother's wedding, and then I came back and broke my leg, which has left me laid up and less motivated to work on my peripheral blogs.

But this is one of my favorites, so I couldn't stay away for too long.

And, this book, Howard Zinn's must-read history told from the point-of-view of the losers, A People's History of the United States, is one of my favorite books. I bought this myself in 2004 sometime, and I'm pretty sure I bought a few copies, with the others going to close friends. It's an updated version that has the 2000 election and the War on Terror, going up to 2002.

Any honest history class should have this book, or sections of this book as needed for counter points. See how Columbus slaughtered the Arawak of Cuba, effectively exterminating them. See how the native opposition to the government worked on the ground. See how...well, let's just say this is an angry book.

Conservative pundits decry it as liberal revisionist history, but the facts of history tend to be ugly and wart covered. Sometimes it's just a point of view. Two of my favorite lines in the book are the opening lines from the chapter on the Vietnam conflict:

"From 1964 to 1972, the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the history of the world made a maximum military effort, with everything short of atomic bombs, to defeat a nationalist revolutionary movement in a tiny, peasant country---and failed. When the United States fought in Vietnam, it was organized modern technology versus organized human beings, and the human beings won." (Page 469)

That chapter went goes on to discuss how the Vietnamese were a pain in the butthole for the Japanese, who occupied them during WWII, then, after the end of that mega-war, how the Vietnamese were a pain in the butthole for the French (but also from before the Japanese as well as after), and about how they declared independence and had a constitution and were supported by the US. Until they decided to adopt a more socialist government structure.

That whole scenario got me a little obsessed with Vietnam for a while. All they wanted was independence, from the 1880s on, and fought for it that whole time. They fought China, they fought France, they fought Japan, they fought France again, and then they pushed us out.

In any case, if you want to get angry and feel like you're getting the whole story, this is the book for you. If you want a spike in your blood pressure, this is the book for you. Honestly, I can't read it from cover to cover like I would other books...it angers up the blood.

Howard Zinn, late as of 2010, inspired a slew of "People's History" books, written by experts in certain fields, all collaborated with the Zinn master and covering a wide range of topics. An example I have that'll show up here at some point is Dave Zirin's People's History of Sports.

I like Dave Zirin, and another one his other books that I have, Bad Sports, is another tough, blood-angering tome.

Friday, June 15, 2012

Wordsworth, Coleridge, Melville: Lines Composed Above the Bluffs of Long Beach

Apologizing for the time off, even though there aren't too many readers, I'm guessing. But here I am and here we are and here are a pair of books that come to you by way of a class I had during my senior year of college. I wrote about that class already, in maybe my favorite post from this site as of yet.

But there were other inspirational moments from that English class.

Our teacher provided us with the cheapest editions around, a topic I touched on in the linked post above. In the Melville book we only read "Bartleby".

Now, I'm having a hard time remembering having read the entire story, or novella, because I don't think I did. I do have a pretty firm grasp of what happens in it, because I was somehow focused in class long enough to listen to the lectures.

By the time you're a senior in college, I guess, you've figured the way to pass most classes is to just listen to the teacher and regurgitate the stuff they say onto tests. But I've always felt like going back and experiencing the story for myself.

Bartleby is the name of a guy, a scrivener in the story. The narrator is an old man who runs an agency that employs scriveners. In the time before photocopying, people with good penmanship, low occupational opportunities, and a high threshold for boredom could become scriveners--workers who spend all day copying legal documents and the like.

It was one of the tragic ironic jobs--a writer, for all intents and purposes, but one who never writes anything of their own creation, at least while on the job.

Bartleby, though, not long after getting hired, begins to show up for work but, upon being new assignments, protest to the narrator "I prefer not to." This confounds the narrator/business owner, but he keeps Bartleby employed. "I prefer not to." "I prefer not to..." it becomes something of a mantra and bonds the narrator to Bartleby.

I won't say anything else really, because that's almost all I remember from the lectures. But I would like to check it out again. Melville was way ahead of his time...

We also touched on the Romantics, the biggies anyway, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats...I was able to feel Wordsworth, and even went up to an old dorm hangout one day during this quarter and sat and tried to fashion my own facsimile of "Tintern Abbey..." set of lines, although mine's prose.

I respected Coleridge's wasted talent (pfff, junkies), and liked the stuff he actually finished and it's far out zaniness.

Keats, well, Keats was ultimately the heavyweight, if I remember correctly, having come in a world where Wordsworth and Coleridge were already well known. Too bad he died of tuberculosis when he was 26.

It may have been because of the later timing of the material's lectures, and a serious senioritis-fueled bender, but I don't remember too much of the Keats lessons, besides the names of some of his famous odes, like the Grecian Urn and the Nightingale.

Which is too bad. It's something else on the list of things to get back to. That whole "get back to old things" activity has actually been started, using a book from this exact class, but not one I've talked here yet about.

Uh...okay, so that's how that is...

I do, still today, have a soft spot for that stuff I wrote that day up in the dorm area of campus, aping Wordsworth. It needs a quick edit, and then it'll be even better. I usually resist editing certain things, wanting to keep them captured with all their flaws still speaking to my flaws. Sometimes, though, I have the urge to make one break through, speak to something human, something true...you know, become art...

Thursday, June 7, 2012

Shakespeare and Poe: Necessary Library Staples

These two works, the complete Works of Shakespeare, and the complete works of Eddie Poe of Baltimore, are two things that when I was younger I figured any self-respecting library would have to have.

Is that still the case? Or, rather the question might be, do I still feel that way? Uh, sure. I've dragged these two volumes with me everywhere since leaving Sacramento in the summer of 2000. The Shakespeare book was my dad's, I'm fairly certain, and I snatched it up when I was ready to move back to San Luis. Those books, "the complete Shakespeare", tend to be affordable and easily found in either used book stores or in new volumes at discounted prices at major chain stores...

...Which is how I acquired the Poe volume. I try not to do that anymore, really, buying copies of classic books from big-box-bookstores that have printed the classics themselves--that's really a double whammy attack on the publishing industry: paying big-box booksellers besides indie bookstores as well as not paying a separate publishing house.

In the Poe volume I've read "The Maelstrom" and "The Tell Tale Heart". In the Shakespeare collection I don't think I've read any of the selections. I've used sonnets before for projects, and read a smattering of plays for pleasure and school--"The Merchant of Venice", "Othello", "Hamlet", "A Midsummer Night's Dream", but never from this volume. I used to have a Shakespeare'S Sonnets book, and had other items for each of the plays I read.

It was still important for me to stock both of these books.

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

The First of the Frank Burly Books

These are the first two books in John Swartzwelder's Frank Burly series. They're Swartzwelder's first and third books, sandwiched around the cowboy story Double Wonderful. He's up to 8 as of 2011, each as great as these two, I'm imagining.

Frank Burly is a private detective who's real name is never revealed in these first two books, and who chose "Frank" and "Burly" as names because that was how he aspired to act.

John Swarztwelder is the most prolific writer of The Simpsons, having penned--according to the cover--59 episodes. I've heard him described as a first draft machine. The tone of many of the most beloved early episodes can be attributed to his world vision. That all becomes clear after reading these books.

These are two of the funniest books I've ever read. Well, make that the two funniest books I've ever read. They are really full of laugh-out-loud material, which, for someone who reads Gilbert Ryle and Thomas Pynchon for pleasure, has to mean something.

After hearing about the books while listening to the commentaries on the Simpson DVDs, I found them on Amazon.com and ordered them one at a time from there.

If you like The Simpsons, you must read these books, and frankly, everything by John Swartzwelder. You'll be better for it.

Humor writing is difficult, very difficult, and there are a few of the "famous" humor writers that are pretty good and show up in the New Yorker's "Shouts and Murmurs" feature. They're all right. The two best for my money are John Swartzwelder and an old friend of mine (who's material is very hard to come by) named Pat Yamamoto.

These are two of my favorite books ever.

Friday, May 25, 2012

"Picasso at the Lapin Agile", Steve Martin: "...Comes From the Future..." "Wrong!"

This is one of my favorite books in my library. I bought it while I was living in San Luis Obispo and saw some show late at night about Steve Martin, the comedian, movie star, and writer. Martin got a degree in Philosophy, which made his transition to night-club hopping comedian pretty easy.

They mentioned this book during the program--I don't remember what it was--and I went out and bought it pretty much the next day.

Picasso at the Lapin Agile is a collection of plays that Martin wrote, and my favorite--and the reason I bought the book--is the eponymous "Picasso at the Lapin Agile".

The Lapin Agile is the name of a bar in Paris that Pablo Picasso would frequent. During the actual time that Pablo was living in Paris another titan of the twentieth century had also visited the City of Light: Albert Einstein.

Both men would have been young and both not yet presented the world with their momentous ideas: for Picasso it was Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907) and for Einstein it was his theory of Special Relativity esposed in his Annus Miribilus papers (1905). The play is an imagined meeting of the two most important men of the twentieth century in their respective fields.

The two guys meet at the Lapin Agile, shoot the breeze as only two geniuses can, and we even see Einstein correcting Picasso on his theory of what I call the Ganzebilde. The men don't know each other before, and a future meeting is unlikely, but their time spent together has left an indelible mark on one another.

Steve Martin, a noted art collector, let his feelings about which was more important be known with the title of the play, and eventually, the book. Eh, maybe not..."Picasso at the Lapin Agile" sounds better than "Einstein at the Lapin Agile", and in the play the bar is Pablo's hangout, and Albert does get the last word in their competing theories of the nature of the cosmos...

In any case, the copy of the book has a picture from one of the first productions of the play, and the great casting allows us to imagine how the scene could have looked:

Now, this meeting may never have happened. In fact, it likely didn't. But, in the realm of crazy science guy hanging out with crazy thinky art guy, I have the great pleasure of announcing that such a meeting did happen, and it blossomed into friendship.

Here, the science guy was more of a mad scientist and has actually been labeled the Father of the Twentieth Century, and the thinky art guy was actually a writer, one of America's most beloved:

Oh yeah, man, that's Nikola Tesla and Mark Twain. That'd be a hell of an evening.

Tuesday, May 22, 2012

Pair of Picture Books about Picturing

These two books were purchased at the local Dollar Bookstore at different times. The first would have been very helpful for a piece I wrote a while back about Modern Magic. It has a very nice detailed explanation for how photography works and how it originally developed, pun not really intended.

If you ever would like to explain to someone how light mixed with metals to make images, this is the colorful book for you. If you'd like an idea on what makes for art in photography this book also does a pretty good job with an introducing that subject.

This next book does a better job with that, with what the vocabulary is when talking about photography as an artform. Both books are very cool and very neat looking, even if photography doesn't really interest you.

Friday, May 18, 2012

"Dance Dance Dance", Haruki Murakami: Inventive Fun from Japan

Like other books in my library, this came to me from a trip I'd taken to an independent bookstore in Brooklyn and looked for something to get. It almost sounds like I was keeping indie bookstores open myself through patronage, but that's just silly. I probably visited a handful of indie stores between downtown Brooklyn and Greenwich Village, and tried to make purchases when I had the money and found something I wanted. well, I guess the I picked up Vineland at the place on like 35th across from that Adorama store, and the used M&D...somewhere similar, I'm pretty sure.

Anyway I digress, and neither of those is Dance Dance Dance, by Haruki Murakami. This is not the first Murakami book I read, so I was familiar with his work, and by "familiar", I mean "ape-shit crazy for".

If you've never read any Murakami, I beg you to check him out, and this book is fine to start with, or, another book that will show up here sometime soon, Hard Boiled Wonderland and the end of the World is another great first book to jump into Murakami's inventive worlds.

Murakami, while attending university in Tokyo, decided instead of the profession he was heading into (or might've already been in--I'm a little fuzzy on the exact details) that he wanted to open a Jazz club. And he did. He ran a successful Tokyo Jazz club for a few years. Then, while watching a baseball game, he decided he wanted to be a writer. And he then became a writer. Later on, while not abandoning writing like he did his jazz club, he decided he wanted to be a runner, and is now a successful marathon racer. He quit smoking in his late forties to help with his running...that's the kind of dude Haruki Murakami is.

His fiction is playful and funny and full of weird things you'd think you'd only see in late night sci-fi movies, but fully make sense in the world you're reading. Here's an example of a Murakami short fiction piece I read in the New Yorker: a lady is having a hard time remembering her name, and eventually she's lead to a laboratory where she meets the talking monkey who's been stealing tiny nameplates from people, causing them to become forgetful of their own identities. Silly monkey.

In Dance Dance Dance the protagonist finds himself walking through a scuzzy part of town, and remembers having been there with a girl before, and for nostalgia's sake decides to check out the seedy motel they stayed in that one passionate night, the old Dolphin Hotel. When he makes the turn to street that has the place he can't believe it. Instead of the run-down shambles he finds a brand new and shiny high-rise hotel, bright with lights and flush with cash, but sill named the Dolphin (they might use the French Dauphine, though).

Stunned, he eventually goes up to a certain floor, and when the elevator door opens, he's swallowed by blackness. The floor is pitch black and the air has some character, and at some point he meets the Goat Man and shit gets weird.

I usually consider my own fiction writing style to be a unit sphere nestled about the origin with one axis being Thomas Pynchon, the second axis being Denis Johnson, and the third axis being Murakami.

Murakami's ease of storytelling about weird science-y phenomena, and his confidence and ability to craft stories in which those things just happen, are the things from which I draw. If anything qualifies for sci-lit as opposed to sci-fi, it would have to be Haruki...but even then, it's more than that.

Above all, it's fun to read. I can't say that about all the stuff I've read, even by those writers I really enjoy and try to emulate.

Also, there's another Japanese writer who has made strides in America who's named Murakami, but this other gentleman is Ryu. Ryu Murakami is also good, but in the same way that Haruki is.

Wednesday, May 16, 2012

"The New Messiah", Daniel Biskar: From My Godfather

This was a Christmas gift a few years back from my Uncle Dan, who also happens to be this book's author, Daniel Biskar.

Based in the beach cities of Los Angeles during the mid-'70s, The New Messiah follows Neal, the main character, an idealistic poet who conceives a utopian plan to create a messianic movement. He convinces his charismatic friend Andy to play the part of messiah.

A real problem arrives when Andy starts to believe his own story. Fueled by the cynicism and alienation that's been a staple of American youth culture since Watergate, the movement gains a certain level of prominence. It, like many messiah movements, doesn't last too long, and the last we see of Andy is during his recovery period.

Neal, the instigator of the movement and through whose eyes we readers experience everything, has his own issues with love and friends. Since he's the rock of the group, his friends seem to lean on him in their times of need, and he feels an obligation to help them. He also feels a complex mix of guilt for how the movement evolved and how he wasn't able to stop it after it got out of control.

It's been years since I've read it.

Uncle Dan's style is what strikes any reader: it is written entirely in a play-like format. A series of dialogue blocks and stage directions are how the action unfolds throughout. I wasn't quite sure what to make of it at first, but as I got into the story, I started to appreciate the confidence with which his scenes are presented, and I began to learn a specific way tension can be created.

This isn't a critique of The New Messiah, rather, this is simply about a post about a book in my library, how I came to have it, and how it affected me in some way or how it will help me later in some way--basically the reason I still have it. Since the author of this book is literally my godfather, I feel a certain closeness to the work, and don't feel my library blog the proper place to fully critique it, but I haven't done that yet really with any book. Maybe informally, of course...

This book is great for any young aspiring writer. It deals well with dialogue and tension, and extremely well with minimalist scene setting techniques, bringing playwright tools along and incorporating them into a novel. Plus, the story is pretty cool, one about sex, drugs, rock and roll, and reasoned and deliberate false prophets.

Tuesday, May 15, 2012

"Zap Comix #0", Crumb: From the Streets of the Haight

Changing gears somewhat, I'm putting up a comic that I picked up this past weekend at the Long Beach Comic Convention. I've refrained so far from using comics, as I think that maybe I should start a whole new blog solely for them. This comic is different.

This is a copy of "Zap Comix", #0. It was released after #2 and before #3, but is material written before issue #1 in real time. I found this issue, a fourth printing in "Very Fine (Minus)" condition that I got at half price, and it still cost me nine bucks.

In the sixties, as the return of comic books to a realm that's not quite mainstream media--but still sorta prominent--ensued, certain people began to use the form for stories that were a little more mature and using things like drugs and/or sex as the motivation. They began to be called comix, with the 'X' designating an X-rated subject matter.

Robert Crumb was working in Cleveland as an illustrator in the sixties making greeting cards. He was hating life. Then LSD made the scene in Cleveland, and after making its way to Robert, he was really hating life, because now he was enlightened. One night he met some guys in a bar who were talking about driving off to San Francisco. That sounded good to him, and like so many other heads in the mid to late sixties, he dropped everything and left for the City by the Bay.

And, like so many heads during that time who did that, he found himself on the Haight, just hanging around, twisted, trying to find meaning, and something to do. He started making drawings, and then some comics, and then got a crazy idea.

He decided to write and draw and print and publish his own independent comic books. He and his new wife would walk up and down Haight Ashbury and sell his "Zap Comix" out of a stroller. Eventually they found their way into head shops, and could be purchased that way.

For me, as someone who has read his share of comics, to thumb through an American artifact like this is remarkable: every single pen stroke and mark inside is from one guy, R. Crumb. There are no ads, no editorials (besides the whole thing I guess), and no masthead information. Just a guy doing his thing, an artistic thing he believed in.

It's inspiring.

And, at this time in my life, my connection to comics has entered a more mature phase. "Worth" now is judged more on what it means rather than dollar figures. I've been looking for a copy of Zap #0 for a while, one with the 35 cents price (some really late editions have a 60 cent price), and wasn't completely falling apart. Prices for the very early editions are extremely high. This copy was the best deal I'd found, and it was something I was specifically looking for at the Nerd-Fest. Here's a link to something I wrote about the LB Comic Con.

Comics for me are not investments, and this copy, much like my first paper-back edition Gravity's Rainbow, isn't for sale. This is an artifact, an artifact from an American past that is easily blurred by films, paintings, photos and albums.

Here is a collection of images and "stories" from the time when you could make a living selling a comic on the streets out of a stroller, and it captures the ethos as accurately as you'd expect.

Thursday, May 10, 2012

"The Right Stuff", Tom Wolfe: Straddling the Line Between Brave and Reckless

On my shelf this sits next to my copy of Zodiac, well, at least until I return that one to the Cabin. I think I either bought this copy at that huge used bookstore just north of SOHO in Manhattan, or much earlier. It might have been a quarter book, as in it cost just a quarter. I wish I remembered.

About the only thing it shares with Zodiac is the status of non-fiction. Robert Graysmith, the writer of that other book, was a cartoonist and researcher who wrote that book because he had all the data. It kinda reads like that as well.

Tom Wolfe was a ground breaking journalist who showed that the tools of fiction writing could be used to write non-fiction pieces. He led a journalistic revolution that had/has many followers and disciples, and even shoot-offs like Gonzo journalism, a thing that HST reluctantly birthed into existence.

I remember "reading" The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test when I was in 6th grade, and here by "read" I mean "read most of the words on each page", but you might be able to guess what I took from it.

This book though, The Right Stuff, touched something I was really into as a kid: becoming an astronaut.

It covers some of the ballsiest men in American--or any--history: the test pilots. Chuck Yeager being the top guy, we see how their days go. They come to work and get onto a plane that nobody has ever flown, or, even knows if it can fly. Then they try and fly the bastard. Many of these guys died, and only the most fearless and badass stayed alive.

It was from this crop of guys that the first set of astronauts was taken. Only the cream of the crop was desired, but they mandated that the astronauts have a college degree. Once it came out that there was very little piloting going to be going on, most guys looked disparagingly upon the program. Once the mandate that a degree be held by a candidate came out, thereby denying Yeager, generally seen as the top test pilot, the amount of respect for the program dwindled among the ranks of the pilots.

After the gentleman were chosen, and America's reaction to them was discovered, everybody then wanted to be an astronaut. At first, even the word "astronaut" wasn't taken seriously by the pilots, who refused to use it.

The book discussed the invisible ziggurat that pilots climb during their careers, and how easy it is to fall off and fuck their prospects up. It also delves into the concepts of "Single Combat" and ancient Africa to explain the frenzy the American public was whipped into over the space race with the Soviets.

Such is the outlook and direction of Tom Wolfe. Instead of ending the book with an anecdote about some astronaut, like the film does, with the easygoing pilot falling asleep on the launchpad, he ends it with one from the top test pilot of all, the first man to break the sound barrier, Yeager himself.

I remember reading, and re-reading the final scene a few times on the subway, and then boring my coworkers with it because it struck me as so fantastic, so hyperreal, and right in the character of old Chuck, one of America's forgotten wild men.

Okay, here it is (I fought with myself about whether to tell the story or not): Yeager, now an instructor with the Air Force, hears about a new plane arriving at the base, and decides to take it out for a test--without real permission. Who in the tower is going top stop Chuck Yeager? He gets up into the air and notices certain design flaws, and get the plane into an out of control stance hurtling through the air. His only chance it to stall it out, shoot out the back parachute, get it pointed down, then cut the 'chute and try to jump start it in the fall. He gets all that ready, stalled out and hanging on the parachute, pointing down. He drops the chute, but the flaps were stuck and he was back into an uncontrolled spin. He decides that it over, and finally blows the hatch. He and his chair are blown free of the jet, but the explosive fuel that launches the chair during an ejection sprayed all over his helmet.

It burned through his helmet, and then started burning his face. He's falling through the air, his plane will be crashing in a fiery mess in the desert soon, and his face is on fire inside his helmet, which he's struggling to remove. Finally he gets his helmet off, opens his shoot in time, which dissolves mostly from the fuel, but not too much before slowing down enough to survive the impact with the desert floor. his right eye has been blinded, but, as it turns out, only temporarily. He recovers fully, and the scars on his face don't even hold.

It was Yeager who got the other pilots to finally start to respect the would-be astronauts. While there wasn't a whole lot of "piloting" going on, he pointed out, it took a certain kind of man to sit on a tube of explosives and then light the match.

Still an exciting read, I'd recommend it to anyone interested in an isolated section of the late '50s or early '60s that's devoid of popular-culture connections, or about how the creation of NASA affected the military on a personal level.

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

"The Mysterious Stranger and other Stories", Twain: Feisty Clemens

If you can't read the title of this, it is The Mysterious Stranger and Other Stories. I bought it while in high school because of a show I caught on the Discovery Channel or the History Channel, back when they showed engaging documentary-type shows instead of the reality garbage they produce now, and on this show they spoke briefly about Mark Twain's story about the devil coming to a tiny Austrian town and messing with the people there, and about how he wasn't such a bad dude.

Wow, I remember thinking, I'd never heard of this story before. I searched it out and eventually bought this book. By far the longest story in the book is the last, "The Mysterious Stranger", and I can say that at that young age when I purchased the book, its length intimidated me, and for the longest time remained the only story that I hadn't read in the book.

I'd motored through the rest of them at some point before making the transition to pour soi, so they're true power (or occasional lack thereof) wasn't fully grasped by me. In fact, the only one I remember with any real sense is "The

I probably read that story again after the pour soi transition...I vaguely remember thinking that would be a eat premise when I read about it in The Atlantic one year.

In any case, I finally read "The Mysterious Stranger" while I was living in Brooklyn, as it was one of the various books I read while doing the subway commute. I remember reading some background notes first, like a little history of the piece, seeing as it was last piece and was finally put together by a friend posthumously.

The background story went that Twain worked the ending a few different times, and was never really satisfied with it, and the ending that we see is really an ending that should be with another story, or the transition is not very good. Well, we can agree that a man of Twain's talents probably wouldn't have settled on the ending as it appears in most editions.

I don't want to give too much away, but Satan is a pretty nice guy who molds clay into living things for the amusement of the kids in a small Austrian village, and some lessons about being led to war and indiscriminate killing and subjugation that are as relevant and prescient today as they were in his time, or, really, anytime. That's the power of a great writer.

The ending does feel like it's slapped on and barely connected, but the power of the piece on the whole is there, and it's Clemens at his feistiest.

Here is a link to probably the creepiest claymation rendition of any story around. It may not be fully accurate to what's on paper, but it bizarre and worth looking at, especially if you're into weird creepy shit.

Monday, May 7, 2012

"Fiskadoro", Denis Johnson: Early Novel from a Great Writer

I purchased this copy of Fiskadoro from an independent bookstore in Brooklyn. I had this habit of finding random indie bookstores on lazy weekend walks and checking out their selections, and, if they had something good enough, and I have enough spending money (rarely), I would buy something. I did this in Sacramento, in my college town of SLO, in Brooklyn, and even in Austin.

Denis Johnson is one of my favorite writers; his collection of short pieces called Jesus' Son is a modern masterpiece of the art form, and he's one of the rare writers hailed in his own time by his peers. Maybe his most famous work is Tree of Smoke, a prestigious National Book Award winner about Vietnam. My father believes it'll go down as probably the novel about Vietnam.

Fiskadoro is an early novel by the writer, and you can tell it's an early novel. It takes place after an apocalyptic crash of civilization out on the rather isolated Florida Keys. The mainland they tend to call the wasteland and is avoided by decree. Reading it you try to surmise just how long it's been: there's a music teacher and a semblance of musical or symphonic gang, a group determined to keep some shred of culture alive, while other social moors are rather tossed away, like when women reach a certain age they cease wearing shirts.

There's also a strange group of people living on the island who are called the shadow people, or something, but they're not part of the "normals" world. They're known to take young men and do things to them, to their dicks. This group seems like legends used to scare the kids, until the main character is nabbed and operated upon.

I grabbed the book just now to thumb through to get an idea of the name of the "others", and I realized I can't remember a whole lot of what I was looking at. So take what I've said with a grain of salt. This has been pretty much what I've taken from the story after a five years and a few beers.

I do remember the mother and the matriarch, who aren't the same person. The "mother" is the mother of the main character, and as her kids are now older and she's found a "pebble" in one of her boobs, she finally decides to drop the shirt wearing act. For this she's reminded by another with a laugh that it easily could have been done earlier.

The matriarch of the settlement, grandma, is the oldest person in the story, and has the most recollections of the world before the fall. in a long flashback section we see the real story that Denis Johnson wants to tell; it's a scene from Vietnam.

The grandma character has vivid memories of being a nurse on a fleeing helicopter as it was downed in the Gulf of Tonkin and getting rescued. This character, as a young lady, is very similar to a character from Tree of Smoke, and having read both, and Fiskadoro second, the connection--from my own writer's perspective--in undeniable. The woman doesn't have to be the exact same lady, but the fact that they look the same and act the same shows what's going on in the head of a word artist.

For those who know the following reference, this is similar to, but not as obviously directly used in a different manner, the Porpentine and Goodfellow story "Under the Rose" from Pynchon's short story collection Slow Learner and how it was later utilized in V.. That novel did come out first, and when the collection of stories came out readers and fans were able to see how that material morphed into scenes for V., but started as something slightly different, and here, in a different venue, consist of a story. Almost like a missing scene, or something that adds to the canon.

V....I can't think of any writer's first novel being as......maybe the best novel ever written by a teenage girl, also a first novel, but became more of cultural touchstone than anything Pynchon ever wrote could be in a similar category (I'm talking about Mary Shelley's Frankenstein).

Digressions. Fiskadoro is a good look at a writer growing and using something like a post apocalyptic world--typically a sci-fi or fantasy trope--as a setting for some wacky literature. Check it out if either opf those things interest you; watching authors mature or weird shenanigans on the post-apoc Keys.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)